Anna Shechtman was one of the youngest female crossword puzzle creators to have a puzzle published in the New York Times. She has continued to break new ground by making the crossword puzzle scene more diverse, but has also had to deal with her own challenge with anorexia along the way.

The clue: Grande Dame of music.

The answer: Ariana

It is one of 31-year-old crossword constructor and journalist Anna Shechtman’s favourite clues and reflects the changes she has been making to the crossword puzzle scene.

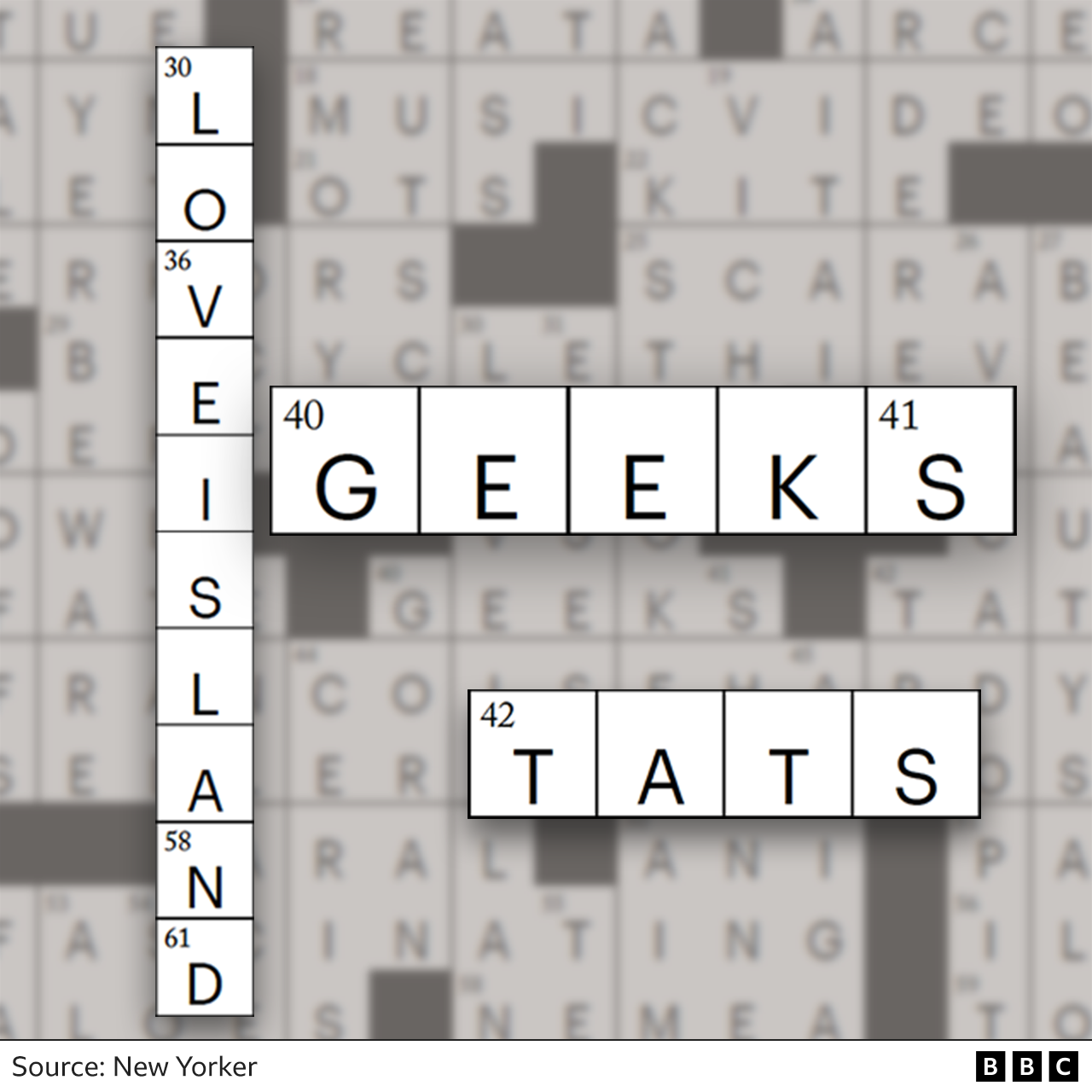

Anna now works for the New Yorker magazine, and with a PhD in English literature and film and media studies, she describes herself as a “very avid watcher of reality television,” including the dating show Love Island.

She has always been determined to make crosswords more inclusive and use language that resonates with a more varied readership.

“Solving a crossword puzzle, there’s a lot of joy in that moment of recognition when you see something you know reflected back to you in the newspaper grid,” she says. “And so for me, it became a project of bringing that moment of recognition to more and more people who look and sound like me and consume the same sort of cultural artefacts that I do.”

Historically, the world of crossword puzzle creators has been very male-dominated. Anna describes herself as part of a small generation of creators who are bringing a more diverse inflection of voices into it.

“I mean every crossword puzzle, in many ways, is an index of its maker,” she says.

Anna grew up in Tribeca, in downtown Manhattan with her lawyer father, art historian mother and an older sister.

“It’s a family that’s very loving and also very sort of New York Jewish in all sorts of stereotypical ways,” she says. “Debate and education were definitely prioritised and so our opinions and our ideas were always really valued from a very young age.”

She first fell in love with the crossword puzzle aged 14, when she went with her mother to the Angelika Film Centre, an indie cinema in Soho, to see a documentary called Wordplay, all about crossword puzzle constructors and devotees.

“The film really introduces you to the very eccentric members of the crossword world, and I had this strange moment of cinematic identification with them,” says Anna. “You have to be a little bit touched to find creative inspiration in a 15×15 grid, and for whatever reason I felt their enthusiasm and their eccentricity pass through the screen.

“There was something about this key to something infrastructural or foundational about language – it was almost like magic.”

Anna began creating American-style crossword puzzles, which differ from the UK grids.

“It’s all about making sure that every single letter needs to be connected to two words in the grid, which is its own masochistic constructing process,” she says. “Much different from the British-style crossword, where the difficulty is really making up those little riddles that encapsulate each clue.”

Anna constructed all her crossword puzzles by hand using graph paper and “many, many dictionaries” until she was about 25.

“It’s almost like words become a kind of maths equation and you have to make sure all the letters interlock on the page while still being real words. Now the process has become digitised and I started using this crossword-constructing software that everyone has been using.”

As the software expedites the process, Anna thought of it as cheating for many years, despite it still requiring a great deal of human input.

“It was understanding basically that I was really making myself uncompetitive as a crossword constructor that I eventually started using the software.”

The first puzzle she ever created by hand was based around the theme “midterm” she says.

“The thematic answers in the puzzle had the word ‘term’ in the middle of them, so that’s the play on midterm – so mastermind, determined, watermelon. I think I gave it to my mum to solve.”

Anna wasn’t sure her family completely understood her passion.

“My older sister would sort of troll me, she just thought that I was hopelessly uncool. She’s come around,” she says. “There were many ways in which I don’t think [my family] totally understood the mechanics of my mind, and many ways in which I didn’t either, but it was very much my own thing.”

Over time, Anna says creating crossword puzzles became “a self-soothing or coping mechanism,” after she developed anorexia in her teens.

Then, her college boyfriend, at the time her “most devoted solver,” sent one of Anna’s puzzles to Will Shortz, the renowned crossword puzzle creator and editor at the New York Times.

“Shortz was really enthusiastic,” says Anna, “and especially because I was 19, he rushed the puzzle to print because he wanted me to be among his teenage constructors. He was very clear, if I made the revisions really quickly I’d be the youngest woman to publish in the New York Times crossword.

“I actually wasn’t that quick because I was doing it by hand and became the second youngest to publish in the Times.”

But alongside this backdrop of the rigidity of the interlocking word grid, Anna was dealing with anorexia. She sees the history of her eating disorder and the history of her cruciverbalism – or devotion to crossword puzzling – as “intimately enmeshed with one another”.

Anna and her family “became quite afraid” by her physical condition, so she agreed to start a process recommended by her doctors called refeeding, in a very controlled environment. She would have three large meals a day and in between write a crossword puzzle.

“I found that there was a kind of escape from the body that happened when I would be writing these crossword puzzles. I’d enter into this sort of virtual word matrix and it gave me a sort of compensatory high,” she explains.

“I understood that what I was doing was difficult and hard and made me feel sort of virtuous in that way, and it also allowed me to escape from the discomforts of embodiment.”

Anna says she loved school, but because of the eating disorder had to take off multiple semesters.

“I really lost the trust of my family, it was absolutely the worst period of my life in terms of not only my own relationship to myself, but also it really ruptured all of these relationships that were so precious to me.”

What was distorting about the eating disorder, says Anna, is that she felt it had become essential to her sense of self.

“What was most scary wasn’t simply gaining weight,” she says, “but actually not knowing who I would be without it. I would have these perverse thoughts like, ‘Well maybe I wouldn’t be as smart without it? Maybe I wouldn’t get as good grades? Maybe I wouldn’t be able to do this niche intellectual activity that was my pastime with the crossword puzzles?’

“All of these things that I valued about myself, I assumed wrongly, deludedly, were attached to my eating disorder, so it made it even harder to recover in that way.”

Anna’s second crossword puzzle was published in the New York Times after she had been admitted to a rehabilitation facility for women struggling with eating disorders, aged 20.

As she started her recovery process, she worried that creating crosswords might set her back.

“With the crossword puzzle, there’s this conceit that you can control this uncontrollable thing called language that to me seemed, again, like the foolhardy attempt to control this uncontrollable thing that is the human body,” she says.

“So when I got back from rehab and really cherished my precarious, but sort of newly-stable recovery, I was worried that it was somehow symptomatic of relapse if I went back to write crossword puzzles.”

Anna says, like everything in her life at the time, she had to “rediscover it and redefine what it meant” to her in recovery.

“Just like my relationship with my mother and my sister had to heal, the same with my relationship to crossword puzzles.”

After she graduated from college, Will Shortz asked Anna if she would be his assistant at the New York Times.

They were very different, says Anna. “He was a 62-year-old who grew up on a horse farm in rural Indiana. I was a 23-year-old who grew up in Tribeca in lower Manhattan – our frames of reference couldn’t be more different.”

Anna and Will would accept or reject crossword admissions to the paper and, once they had accepted them, rewrite up to 90% of the clues. They would sit together, struggling over how to define words.

She gives the example of the word “Bro” as a difference in their approach to their definition of a clue. “What comes to mind for me and what comes to mind for Will Shortz are going to be dramatically different definitions or references,” says Anna.

“His – and this is the way it was clued for years in the Times – was something like, ‘Sister sib, relative of sis. And my clue was something like, ‘Party-loving, narcissistic young man in slang.’ Maybe it would be ‘bruv’ in the UK – one of the many terms I’ve learned from my devotion to Love Island.”

Anna describes having “amicable” arguments with Will, but ultimately says they would both be thinking about the audience, and who they imagined as the “average solver” of the New York Times crossword puzzle.

As Anna’s recovery continued and her journey from writing crosswords transformed from a “private and therapeutic” activity to a more “public and even political exercise,” Anna says she began to understand herself as a “real outlier in the crossword puzzle-making community”.

But she also discovered there had been some female trailblazers before her, such as Margaret Farrar (1897 – 1984), whose genius with the crossword puzzle saw her become the first crossword puzzle editor for The New York Times.

“The other woman who I really admire is Julia Penelope,” says Anna. “She is a linguist and was writing her own puzzles that she deemed lesbian-separatist crossword puzzles filled with words like herstory and womyn spelt with a y. She could not get her puzzles published in the New York Times, and so she self-published a collection of puzzles that I really love.”

Although Anna has been at the forefront of a new generation of more demographically-diverse crossword constructors, she says it has also been wonderful to imagine herself as part of this long line of women cruciverbalists.